Inner-city Johannesburg is an open-air gallery and international street-art destination – and it’s right here in our backyard. Graffiti writers work by the light of streetlamps and conceal their identities because of strict by-laws that govern vandalism to private and public property. Yet the walls of inner-city Joburg – especially Newtown, Maboneng and Jeppestown – are a palimpsestic, open-air street gallery, with playful and poignant masterpieces that comment on the economic, political and social realities of life in the City of Gold. Some have remained intact for years, attracting local and international graffiti writers, and the city is at the top end of worldwide graffiti destinations to visit.

On a graffiti and street-art walking tour through Newtown with Jo Buitendach, co-founder of Past Experiences, you may come across work by international graffiti writers alongside those of local street artists such as Bias, Mars, Fin and Rasty. As we’re led along Henry Nxumalo Street, beneath the vividly painted highway overhead pass and into Gwi Gwi Mrwebi Street, we enter into a technicolour world of wonder. Price’s Candles Factory, for instance, was built in 1910 and is covered from one end to the other in mostly candle-related graffiti masterpieces, with the owner’s permission.

I wrote this article for the May 2015 issue of Mango’s inflight magazine (Juice).

Graffiti originated in ancient Greece and Egypt, but its contemporary variant is a misunderstood art form with a poor reputation. But this is not the case in South Africa. While some consider graffiti to be visual pollution that decreases property prices and encourages vandalism and petty crime, Jo aims to foster an understanding of and appreciation for street art by recounting graffiti’s contemporary beginnings in New York in the 1970s to its rise in post-apartheid South Africa in the early 1990s.

And who better to introduce you to graffiti’s inner world than Jo, who’s writing her Master’s on the graffiti by political prisoners and gang members in Constitution Hill’s isolation cells? She partners with graffiti writers Bias (@intotheabis) and Mars (@mars_graffiti), who provide insight into their work and graffiti culture. “Graffiti outside New York is mostly an adaptation of what they were doing there. South African graffiti is a mishmash of European and American styles, with personal influences from the artists and their surroundings,” says Mars. In South Africa, it has a raw and sharp style that reflects third-world circumstances, says Bias.

Today, graffiti is part of popular culture, even if some examples are anti-establishment or provocative. For many like Bias, who is an archaeology PhD candidate, graffiti is a way of expressing himself. “I try to make my masterpieces as colourful and contextual as I can,” he says. “I also aim to uplift the area and its community.”

It’s difficult to be a full-time, professional graffiti writer: while the best are commissioned by big corporates for advertising campaigns, film sets or personal projects, most do it as a part-time hobby for the creative challenge and collaborate in so-called crews. Many Joburg street artists have degrees in fine art or are print makers, graphic designers, tattoo artists and entrepreneurs by day.

Bias suggests that people see some forms of graffiti as vandalism due to tags, which is a graffiti writer’s quickly executed personalised signature. “People don’t understand their purpose and think they are messy. Nine out of 10 people say: ‘I love the colours, but I hate the messy scribbles.”

Joburg’s graffiti by-laws are not as strict as those in other cities such as Cape Town and Durban. In the Mother City you can be fined R15 000 for a first offence or three months’ imprisonment, with charges doubling for a second offence. While a Joburg anti-graffiti rapid-response unit has been rumoured, neither Jo nor any of the graffiti writers I spoke to have encountered it, although masterpieces have been removed (or buffed). “This place has got bigger problems to worry about than pretty pictures on the walls,” says Mars.

Graffiti writers need to receive permits from their municipality and permission from neighbours to paint legally. “It’s pretty relaxed to paint graffiti in Joburg. There are many walls to paint and communities generally appreciate what we do,” says graffiti writer Rasty (@rastyknayles). “If you’re bombing (painting many surfaces in an area) and tagging at night or doing graffiti on a wall you don’t have permission for then you can expect the cops to stop you and possibly arrest you. Some have got away with a slap on the wrist and others have been charged with malicious damage to property. Only one artist I know of actually served time, but others have been served with a fine or community service.”

The fear of being caught is why graffiti writers remain anonymous by taking on an alias, which usually represents their personality. “I call myself Bias because it represents the dichotomy of the world in which I live. What I see as art, others see as an eyesore,” he says. “I feel the bias against graffiti as an art form needs to be broken down. I want to educate people about the possibilities graffiti can offer.”

Over the years, Jo has already witnessed changing perceptions: “We can see it by the amount of people requesting graffiti tours, films, documentaries and books,” she says. Aside from Past Experiences’ graffiti walking tours, you can also do a freehand graffiti workshop with Two by Two Art Gallery. “I recently travelled to Barcelona just to see graffiti and many people are doing the same. They plan their holidays to see and photograph graffiti and view work by their favourite artists.”

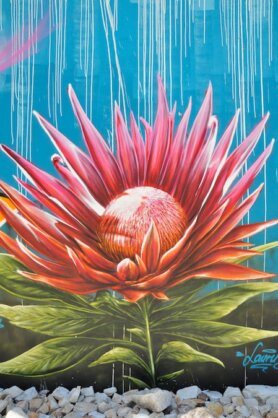

While the street-art scene remains male-dominated, more female street artists are emerging, such as Fin (@CosmicLuckyBag), who majored in printmaking at Wits University and was encouraged to try painting by her friend, classmate and fellow street artist Miss Propa. “It was due to a general lack of interest in the Joburg fine-arts scene at the time (2009),” she says. “It’s not that there wasn’t anything worthwhile happening, it’s that nothing struck me as interesting or personally challenging, after having recently graduated art school. I also found it hard to relate to the art world and what was being produced in the secure, detached, walled-up studios.”

Rasty and his Pressure Control Project (PCP) crew – Curio and Angel – recognised this need and established the Grayscale Store and Gallery in Braamfontein. “It provides a platform for street artists who have spent years mastering their craft but – because of the nature of their work – cannot get their work into mainstream art galleries,” he says. It also shows visitors the uplifting aspects of street art.

PCP also founded the annual City of Gold Urban Art Festival. They invite international graffiti writers to collaborate with local artists and promote Joburg as a street-art destination. Local graffiti writers, along with Jo, volunteer their artistic skill at nearby communities, the Viva Foundation Township Art Project and Soweto orphanages. “Graffiti is fantastic because it’s art in a public space for anyone to experience and interact with,” Jo says. “Many inner-city children and adults have no experience with art at school, but graffiti is all over.”

Jo points to a section opposite Price’s Candles Factory, comparing it to a street-artist’s guestbook. It’s a bright hodgepodge covered in tags, painted characters and wheat-paste posters, layer upon layer of past (and present) experiences. Who knows, perhaps after one of Past Experiences’ graffiti workshops, you might find my tag here soon, too.

Want to go on a graffiti walking tour through Johannesburg with Past Experiences?

Call: +27(011) 678-3905

Twitter and Instagram: @PastExperiences

By female street artist Fin